When I recall growing up on Bath Island (twenty miles of open water from Vancouver and adjacent to lovely Gabriola Island), memories are as much about being on the water as being on land. We were in and out of small boats all day long. All supplies came from Gabriola or Vancouver, often balanced precariously to maximize a load. And during the school year, my sister and I made regular one-mile passages to nearby Silva Bay where we caught the school bus. Year-round we went to Silva Bay for supplies or, eventually, for part-time jobs in the marina. And we fished and went on expeditions for oysters, clams, driftwood, and even Christmas trees in our 14’ clinker-built open boat. She had a 5 horse Briggs & Stratton motor, and was pretty seaworthy. We knew how to choose routes that avoided the largest of waves when the wind blew hard down the Strait. Basic boat and engine maintenance chores were a daily routine – and we rarely went anywhere without a spare spark plug tucked into a pocket or purse. When we returned to the island in the dark, my mom always put a coal oil lantern on the dock to provide a welcoming spark of light.

Bath Island in the foreground, with Gabriola Pass in the background. Far in the distance is Vancouver Island. Silva Bay and Tugboat Island are approximately one mile away, off the right side of the picture.

There were many times, particularly in winter, that we were reluctant to go out in heavy weather — it was wet, cold, sometimes scary — but that rarely stopped us. We’d hide behind the small windshield, protected from the worst of the wind, rain, and snow. And when fog obscured familiar landmarks, we relied on a compass and kept the wind on a consistent angle to the boat. But there were many more times when being on the water was the most glorious part of the day. For one thing, once my sister and I mastered boating skills around the age of 10, we loved our independence. Mom later told me she never knew if we arrived safely at Silva Bay until we returned home. Endless distractions on every passage included other boats, whales, fish, otters, and myriad birds. Occasionally we’d find something interesting to salvage, and every now and then someone would need help. Calm night passages were memorable – a magical combination of the canopy of stars reflected in trailing streams of bioluminescence.

For all that my family was constantly on the water for over twenty-five years, we only had one truly frightening mishap. I set out one windy February morning so that I could write an exam at a college on Vancouver Island. Spray from a wave slopped over the side of the boat and doused the engine. I couldn’t get it started and was pushed downwind to the rocky shore of Tugboat Island. Rather than just going ashore in the pounding surf as I expected, the boat capsized as it hit the beach and trapped me underneath. It took a while to squirm out from under the boat in the rough water and scramble up the sandstone beach. I was fortunate that I went aground on the only nearby island that had a caretaker who was able to summon help. The boat was badly damaged, I had a cut on my hand, and my new leather coat (paid for with wages from waitressing at the marina) was ruined. Ironically, my exam was cancelled due to snow. My parents talked of selling the island, but chose not to. And we all gained respect for the importance of care on the water.

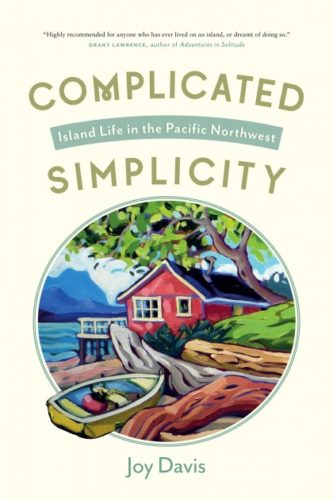

These memories — and many others — prompted me to write about life on Bath Island. I still live on an island – Vancouver Island — where life is shaped by ferry schedules, beaches, seascapes, and a sense of being apart from the mainland. But I am particularly interested in the experiences of people on much smaller islands where approaches to life are more distinctive, at times difficult. I have woven my family’s stories with those of other islanders from archipelagos scattered around the shores of Vancouver Island in Complicated Simplicity: Island Life in the Pacific Northwest. A wonderful part of this process was talking with over twenty fascinating islanders who live without ferry service, much as my family has done over several decades. As many readers of Women Who Live on Rocks know, the need to be in and out of small boats on a regular basis adds a layer of complication to island life because you have to rely on your own boating skills, the right boat, secure moorage, and favourable conditions.

On Vancouver Island

There were many times in my long conversations with the islanders that I laughed at the similarity of experiences we’ve all had. A wonderful mix of seamanship, ingenuity, independence, and a bit of foolhardiness emerges as people shared stories about their on-water experiences. Pondering the most appropriate boat, along with budget and needs, is a big preoccupation. I know my Dad constantly tested new boats though I’m not sure he ever found the perfect one. And choices that other islanders describe vary in fascinating ways. One woman plans to sell her motor boat and buy a rowing dinghy so that she “doesn’t have to monkey wrench anymore.” A young couple uses a kayak for everything from transporting bicycles and bales of insulation to making their way to the maternity ward of the nearby hospital. Another fellow uses a Panga, imported from Mexico, because its high swept bow and buoyancy helps negotiate enormous swells that sweep around his exposed west coast island. He knows that guests are likely to get wet in the process of landing on his beach, so he keeps a sauna primed on the island to warm them up. And a couple on a remote island far up the coast have built a shallow-draft catamaran for both daily transportation and cruising. They love telling the story of coaxing their horse into the cockpit, then sailing ten miles to their island. And one of my favourite stories is told by a woman whose mother used to row her across tidal rapids every morning to catch the school bus. As she says, “Believe me, I was a cherished child. She’d wrap me in blankets. I’d have a hot-water bottle at my feet and I’d have an umbrella over my head—and she’d be out there rowing in the rain and snow.”

Islanders also talked about the slow process of developing confidence in messing about in boats. My mom became adept at handling small boats, but never assumed the role of skipper of our 37’ sailboat since that was seen as my dad’s role. And a woman who moved to remote Rendezvous island from an urban centre told me how challenging it was to learn seamanship. Initially, she was completely reliant on her husband to ferry her about. She felt isolated until she made the effort to take their boat out on her own. And once she had learned the skills needed to operate her boat in increasingly difficult sea conditions, she encouraged other women in isolated locations to do the same.

“Most of the time they were content, but they had to ask their husbands if they could go to book club or pop down the channel for coffee with a friend on the next island, even though it was only going be an hour-long visit. He’d have to come along and hope there would be other men around, or another distraction while his wife was in visiting. And if the menfolk went away for work in logging camps or the oil patch, women were stuck in these little coves and inlets, all by themselves. They couldn’t get out unless they begged a ride from a neighbour.”

The Ladies’ Skiff Club that she created is a wonderful example of how women living in a remote cluster of islands came together on a weekly basis to practice everything from maintaining engines, to anchoring, navigating tidal rapids, and docking. Now, as one woman says,”We can say to our hubbies, ‘See you later, I’m taking the boat.’”

I loved my long conversations, often with women, about the challenges of creating viable docks, maintaining mooring buoys, and figuring out where to put boats while on the mainland. There was lots of laughter about complications. But there weren’t many stories of disaster — although several islanders observed there is a lot of learning going on while they’re on the water. I know that all the skills that I gained getting to and from Bath Island have stood me in good stead over the years, both on and off the water. Finding your way around in small boats is one of the many pleasures associated with life on an island – but for the many islanders who don’t have ferry service to make provisioning, socializing, and connecting with the mainland (relatively) easy, I came to understand it is one of the most complicating factors of a simple island life.

You can find more details about the book here. It is also available on Amazon and other online bookstores.

2 Comments